One Flew Over the Regex Match

A Beginner’s Struggle to Understanding Regex

At first glance, regex can feel overwhelming and intimidating.

This syntax is not for cats! Oh, well, let me Google up some guides… So… \S is a non-whitespace character, . is any single character, \w is a word character, yada yada yada and then…

\b[A-Z0-9._%+-]+@[A-Z0-9.-]+\.[A-Z]{2,}\bis a more complex pattern.

You don’t say!

Why is regex so hard to understand for beginners? For one, regex doesn’t read intuitively: it is neither words nor mathematical equations. Instead, it’s a bit of both jumbled together. It is generalized in a way there are no simple equation signs between the regex alphabet and the literal alphabet. In fact, the word character \w is not even limited to letters as it can also match to an underscore or a digit.

Herein lies the next problem; when you start learning a new language, usually the books or apps you’ll be using are written in your mother tongue or other language you have a good command of. With regex, a lot of the tutorials will throw terminology like ‘non-word character’ or ‘non-whitespace character’ at you, as if trying to teach you by giving you a dictionary of Regex - Ancient Greek. (If you are fluent with Ancient Greek, congrats! If not, oh well, so sad, too bad…)

Another brain twister in learning regex is that \ can either be a part of a special character like \w, or \n for backreferencing the nth captured group, or it can be used to escape a special character to turn it into the literal character. For example . in regex means any character, and \. is used to match to an actual period in the text.

The same goes for ? which appears in several different forms throughout regex expressions, denoting non-capture groups (?:), optional matches ?, if - then conditionals (?(regex)then|else), both negative and positive lookaheads (?!) and (?=), respectively, and much more. While trying to decipher regex, I realized that characters I have learnt to view as punctuation or mathematical operands should be treated like letters and never interpreted alone, but by what they are connected to.

The best way to comprehend something as foreign as regex is to either experiment with it on Rubular or reading through an interactive tutorial such as Regexone where you can immediately try out what you’ve learnt. Both of the aforementioned sites are excellent tools for spotting what you think you already understood, but didn’t really. For example, I thought that \b([^abc]) would match any first letter of a word except a,b, or c, but it actually matches any word boundary followed by any character that is not a, b, or c. Wait! Isn’t that the same as what I just wrote? No, because it will also match the space coming after any end of a word! A space is also a character that is not a,b, or c. In other words, if you use the [^abc] expression, you are not limiting yourself to the character class of a,b,and c, but are truly referring to any character but those three!

Testing out your expressions will also give you a clearer view on whether you are matching to whole words or substrings within words. This is something to be mindful about unless, of course, you won’t mind offering splatter punk instead of comedies (/laughter/ matches also slaughter) on your latest movie-finding app, or are prepared to pay the ticket for driving into a lieutenant parking instead of tenant parking as per instructions in your location services app! \w{3}\ matches any three consecutive letters, underscores or numbers in any length of a word; if you want to find words of exactly 3 letters long, use word boundaries or non-word characters such as whitespace characters to specify that: \b\w{3}\b.

As regex expressions start slowly making more and more sense, a sudden impulse for philosophical pondering hits me:

So, how can the computer tell the kitten apart from the snow? For a human this might seem obvious, but a computer needs to be told how to identify both the borders between snow and the kitten as well as the shape of the kitten in clear terms. In regex, text can be viewed by alternating patterns of word- and non-word characters. Like clusters of letters and digits separated from one another with spaces and punctuation. Alternating vowels and consonants form stripe patterns into a word, dots and @s are the joints of an email address. Maybe the question is not “Why is regex so difficult to understand?” but “How can the human brain determine borders and patterns so effortlessly?”

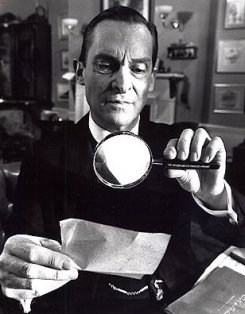

Jeremy Brett as Sherlock Holmes - Image Source: Wikipedia

The First Step Beyond Basics: What Are Backreferences and Capturing Groups?

To be able to understand backreferences in regex, one has to first understand how capturing groups work. In regex, we capture matched patterns into groups by surrounding them with parentheses. For example, let’s try regex expressions on this classic poem

Cats sleep anywhere, any table, any chair.

Top of piano, window-ledge, in the middle, on the edge.

Open drawer, empty shoe, anybody’s lap will do.

Fitted in a cardboard box, in the cupboard with your frocks.

Anywhere! They don’t care! Cats sleep anywhere.

Eleanor Farjeon (1881 - 1965)

- matches the word Cats with one non-word character following it: “Cats “

- captures

Cats&Cats

- matches words that are followed by an exclamation mark, here “Anywhere!” and “Care!”

- captures

Anywhere&care

- matches words that have two adjacent identical letters: “sleep”, “middle”, “will”, “Fitted”, and “sleep”

- captures

e,d,l,t, ande

Great! So we captured some letters. What of it? The point is, when you capture a pattern you can reference back to it and catch a bigger fish. Let’s take a closer look at the last example: we saw that it matches to any word that has two adjacent identical letters, but how does is do that? \1 is a backreference to capture group number one in each individual match. Therefore, (\w)\1 looks for two identical word characters in the pattern, regardless of what the exact character is: ee, 55, and nn will all be matched.

Note that the groups are always numbered from left to right. Correct numbering is crucial for any form of successful backreferencing. To clarify this issue, you can test both the matched result as well as the captured groups for your expressions on Rubular. For example, if you would like to add groups for whatever reason to the last example, eg \b(\w*)(\w)\1\w*\b, the code would break as \1 is now referring to group (\w*). To keep your second group in the code, you could either change the reference number to \2 => \b(\w*)(\w)\2\w*\b or mark the first group as non-capture group with (?:) => \b(?:\w*)(\w)\1\w*\b Voilà, now (\w) is again the first captured group!

Bonus: what does /(.)(.)\2\1/ match?

Backreferences are extremely helpful in matching for repeated patterns. For example, imagine that you got the sudden urge to find data for all the animals that have a tautonymous name from a humongous taxonomy datadump. A simple pattern search with \b(\w+)\s\1(\s\1)?\b will find our friend the lynx (lynx lynx), the red fox (vulpes, vulpes), the european eagle owl (bubo bubo), the western lowland gorilla (gorilla gorilla gorilla), and many others without having to get loopy with it by scanning each letter, or worse still, having to type out the exact name for each species for matching.

Little by little, regex is starting to make sense to me. Admittedly, there’s still a lot for me to learn, such as positive and negative lookaheads and what is really under the hood of the regex machine, what different flavors programming languages add to regex, and so forth. However right now being able to solve this is good enough:

Feeling like a pro! Try it yourself here.

An Afterthought — “What do we need nuclear power plants for? I just had a chat with the girls and we know no one who uses nuclear power. We have electricity, let’s use that!”

During our first weeks of learning how to code, not much emphasis needs to be given on how efficient your code is. As the number of lines in the code we write increase, I can’t help but to think, whether the way we choose to solve a problem with will eat up a lot of processing power? Regex is said to be powerful, and it does save you from writing explicit looping structures, but what does the regex machine under those short pattern matching expressions actually do? Recently, Stackoverflow reported that their site was KO’ed for 34 minutes due to a regex expression dealing with a malformed post with large number of spaces. To a newbie coder this case teaches that even if your pattern matching doesn’t look like a loop, it might still work like one.